If the Transition Trek method of getting to sleep has made everything better, what is the problem? It is the inspiration thing. We actually do gain insight and solve problems while in hypnagogia even though it can contribute to emotional instability when we get lost in insecurities and conflicts. Through the decades, I have developed a strongly directed creative relationship with hypnagogia and hypnopompia. And it isn’t just me. Here’s what Peter Schwenger’s research led him to believe:

If the writer’s inspiration is in some fundamental way insomniac, it follows that for all the complaining there is a desire to be sleepless, to reap the rewards of insomnia. [Page 72]

And it isn’t just writers. I have found that for many of us with insomnia an aspect of ourselves wants to be awake during the middle of the night. I miss being awake so I can write and stew over issues that interest me. When I first go to sleep, I miss ruminating over what had happened that day and try to gain perspective on it. I also fantasize and enjoy engaging in what bubbles to the surface. I don’t miss the worrying although something within me misses it a great deal and keeps trying to drag me back into it.

Even though prolonging hypnagogia can have a negative impact on your sleep propensity curve and your emotional state, this doesn’t mean that you should never spend a little time before sleep working on a serious problem you need desperately to solve. When we do have a problem that we know is going to keep us awake regardless of the Transition Trek and that we may need our deeper resources to solve, we can still ruminate on it prior to sleep. Set aside a few minutes to do some deep thinking, but keep it to one subject if you can and go into it with a specific objective. This will hopefully let the air out of the big worry balloon, so to speak, but once it reaches a point of self-indulgence, you should cut it off.

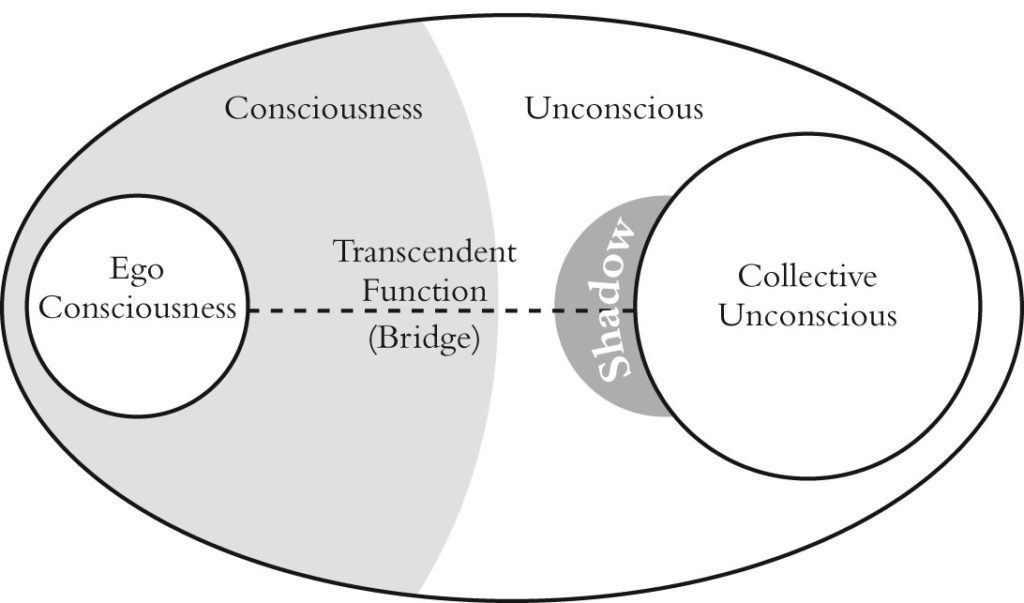

Worrying is a problem that goes a lot deeper than you might imagine. When you take a contentious issue into hypnagogia, you work that problem with the help of the unconscious. The unconscious, according to Jung, consists of personal (shadow) and collective areas, as shown in Figure 9-1. We created our own personal unconscious when we were becoming socialized. It is the uncivilized parts of ourselves that were problematic and suppressed. Later in life, these unresolved issues surface again and work their way into our lives inappropriately. This is where therapy comes in. Therapy resolves those issues left open-ended as we ascended through childhood and became adults. Much of the shadow’s content is reassessed and reintegrated with our better angels so that we become a more whole person. This is what Jung called the “individuation process,” and involves building a bridge — named the transcendent function — from the unconscious into ego consciousness so that we might function better as individuals. We become “individuated.” The changes we undergo are not always what those around us like to see, but we do become more fully who we are and hopefully suffer less internal distress. We build the transcendent function through deliberate controlled contact with the unconscious. This is not something you want to get into while trying to go to sleep.

Figure 9-1 Psychic Space

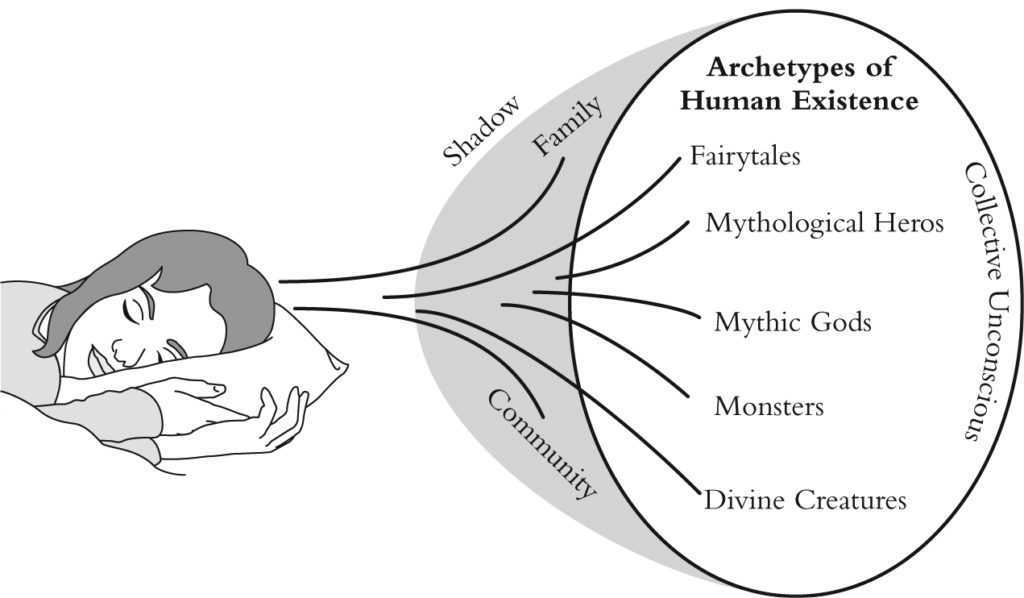

The collective unconscious is inherited and contains the archetypes of human existence. It is the same in us all. It contains a lot of monsters and myths, but it also contains science and mathematics, the arts, all culture really, and enables us to understand and interpret the material world and each other. We also learn to build a relationship with it — again, through the transcendent function — where we gain inspiration. We use the collective unconscious all the time because it helps us interpret information from the senses and form our relationship with the external world. We have a closer relationship with it while in hypnagogia, and if we learn to control hypnagogia, we can gain insight into practically any subject, including the spiritual world. Our relationship with the collective unconscious helps determine who we are and how we form our relationship with the external world.

Figure 9-2 Hypnagogia Disturbances

These two components of the unconscious contribute mightily to the images and voices we hear during hypnagogia and hypnopompia. The worst aspect of allowing our minds to freewheel during these moments of transition to and from sleep is that they can inflate our worries and conflicts far beyond their rational significance. If we use a guided approach to deal with these transition states and enter them with a purpose and an understanding of what resides there, they can be of enormous benefit. Directed and limited activities targeted toward these problematic issues can be productive if they have a specific objective and are not allowed to wallow in insecurity and uncertainty. However, even a reasoned, measured entry into these deeper recesses of psychic space can run into trouble because much of the collective unconscious is an uncharted wilderness.

Destructive diversions into the unconscious also have echoes that reverberate for several minutes. Once started, these processes are difficult to shutdown, and they pull information from the unconscious that can affect your entire night’s sleep, including dreams. Remember, they have physiological components that linger long afterward. Plus, they diminish the importance of the Transition Trek. My advice is to stick with the narrow path of the Trek from the very first, and you’ll have a much better chance of getting to sleep and staying there. Be disciplined. These delays, if they are prolonged, also distort your sleep propensity curve and you will once again experience insomnia. Once you’ve crawled between the sheets and psychically centered yourself, get on with the business of going to sleep.

Myself, I have found that not permitting all this worrying during these transition states has led to more emotional stability. I find it best to worry during the light of day where reality can oversee the discussion rather than within these deeper, ungovernable resources of the depths. I found this to be true late in life. I can’t begin to imagine what a difference it would have made for me if I had found this technique for controlling my nighttime thoughts when I was young.

Another prudent choice to using the creative aspects of hypnagogia and hypnopompia might be to restrict these sessions to the last period of hypnopompia in the morning. At that point, you already have a full night’s sleep, and indulging in a creative activity boots the mind into those inspirational resources. You can plan this session prior to going to sleep the previous evening.

As for conducting these efforts in the middle of the night, I have mixed feelings, and this is where the hard choices come in. If you do it for any length of time at all, you start negatively impacting the sleep propensity curve, and the effects ripple into the future. I have written during hypnagogia for as much as four hours at a time and practiced this for decades. Even when I got eight hours sleep — four before writing and four afterward — I was tired the next day. Sometimes the work I accomplish was amazingly creative and worth the hit the next day.

Too Much Sleep

When getting too much sleep becomes an issue, you know you have made a serious impact on the insomnia problem. I have run onto this situation during periods of little stress and have a few days off work. The problem with getting too much sleep is that it tends to flatten out the sleep propensity curve, and you end up spending most of the time in REM. Plus, you can become addicted to sleep. When you are sleeping too much, you don’t access the really deep stages that contribute so much to your wellbeing. This can also lead to social problems when you become more interested in your dreams than being around friends and family. Balance is an important aspect of life. Or as the ancient Greeks put it: Nothing in excess.