You have tried closing your eyes and letting sleep come to you, but waiting for sleep for some is like waiting for Godot, and when that pale light in the East starts to brighten, you realize the Sandman isn’t coming, and you are in for another groggy day. Perhaps sleep had reliably come to you for decades, but now something has changed and not for the better. You started mindfulness meditation, and you have developed and maintained good sleep hygiene. You now make a “letting-go list” and practice the 4-7-8 breathing exercise before you attempt to go to sleep. You bought a cellphone app, maybe two or three. Even some heart monitoring electronic equipment. You keep a sleep journal. All this even helped a little, and yet, didn’t actually get to the core of the problem. You have tried cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) and rather desperately tried “counting sheep” in the hopes that the old banality had some scientific basis. Nothing really solved your insomnia. The problem is that you are still waiting for sleep to come to you, and you need a more proactive approach.

Circadian Rhythms and Sleep Propensity

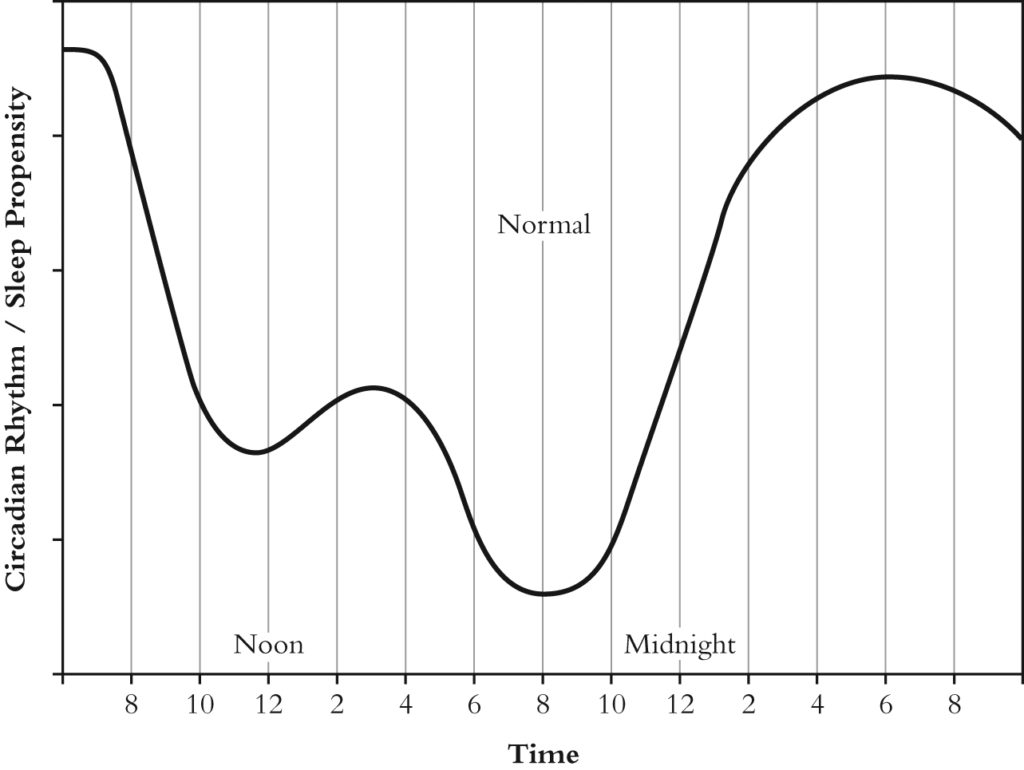

Circadian Rhythms are human biological clocks that predispose us for activities at certain times each day and are primarily configured by sunlight. Sleep is one of these activities. We sleep approximately one-third of each day, and our circadian rhythms are set to provide that sleep propensity at night. See the “normal” propensity curve in Figure 1-1. The other thing is that when we first awake in the morning, our sleep propensity is in continual decline, with the exception of a small hump during siesta time in the afternoon. It starts to build in the evening, and by late evening, it should be irresistible. If you can’t get to sleep when you first go to bed, the problem is termed “sleep onset insomnia.” When you wake during the night and cannot get back to sleep, the problem is termed “sleep maintenance insomnia.”

Figure 1-1 Sleep Propensity/Circadian Rhythms — Normal (Data from “Important Underemphasized Aspects of Sleep Onset,” by Roger Broughton from Sleep Onset ed. by Ogilvie and Harsh.)

Older people tend to go to sleep earlier in the evening and rise earlier. They generally get less sleep although their need for sleep is the same as the rest of us; therefore, they may have an even greater need for a reliable method of getting to sleep and remaining there.

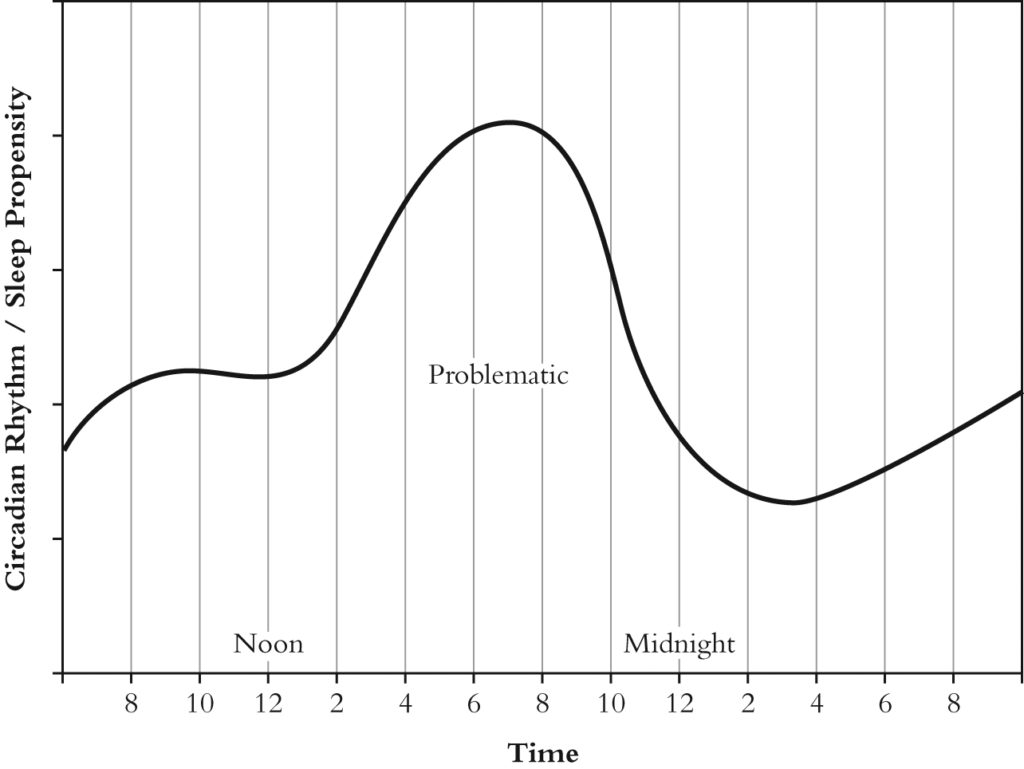

Figure 1-2 Sleep Propensity/Circadian Rhythms — Problematic

The sleep propensity profile of Figure 1-1 is the primary background influence for all of our sleep activity. It provides the impetus to sleep. At this point, you cannot even come close to understanding how important this circadian rhythm/sleep propensity chart is. But the “normal” curve in this chart is for “normal” people. If you’re having trouble sleeping, this is not you. Your sleep propensity curve probably looks like the “problematic” one of Figure 1-2 where the propensity to sleep is highest in the afternoon and only moderate at normal sleep times. This is a hypothetical estimation of your sleep problem, but it doesn’t tell you how you got so messed up to begin with or what to do about it. Can it even be fixed? Or is that just you? Born that way, and the problem destined to be with you forever.

What History Tells Us About Sleep Propensity

While the normal sleep propensity curve of Figure 1-1 gives us a good idea of our sleep habits today, in the not too distant past this was far from the case. Before the Industrial Revolution and the invention of electricity and electrical lights, our nocturnal habits were quite different. Historical research has revealed that we predominately used to sleep in two four-hour segments, separated by an hour or two-hour stretch of activity. The first segment was termed “dead sleep” and the second “morning sleep,” and this segmented sleep was not seen as abnormal. According to researcher A. Roger Ekirch:

“…the vast weight of surviving evidence indicates that awakening naturally was routine, not the consequence of disturbed or fitful slumber.” [Ekirch, A. Roger (2006-10-17). At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past (p. 302). W. W. Norton & Company. Kindle Edition.]

This means that for many people, their propensity curve had been reshaped to fit that sleep pattern, i.e., they had a low propensity to sleep in the middle of the night. Ekirch also says that:

There is every reason to believe that segmented sleep, such as many wild animals exhibit, had long been the natural pattern of our slumber before the modern age, with a provenance as old as humankind. (p. 303)

However natural the segmented sleep pattern might be, one thing is certain: sleep propensity is malleable. To a large extent, it can even be reset to the inverse of the Figure 1-1 normal curve when a worker goes on the nightshift. Even the one-hour shift that occurs as a result of daylight saving time presents problems. Of course, with our highly mobile society, travelers going through several time zones end up with what we call jet lag. It can take several days for the traveler to adjust the sleep propensity curve to a new location several time zones from home, but they do adjust. Anything that repeatedly disrupts your sleep at the same time during the night can alter the curve and not always in your favor.

Regardless of the reason, waking and staying awake during the night can negatively influence sleep propensity and predispose you to have problems at those same time periods the next night and strengthen the problem thereafter. I have experienced a predilection for waking at certain times because of repeated interruptions. Getting back to sleep quickly can help heal these “holes” in your propensity curve and provide you with a better night’s sleep.

The Key to a Solution

You have undoubtedly searched the Internet for methods of falling asleep, but the suggestions you found did not even address what actually goes on inside the mind while falling asleep. So-called experts talked about deep sleep and rapid eye movement (REM), which occurs while dreaming and a long time after you have gone to sleep. They addressed the physiological aspects, encouraging you to practice calming techniques and to ensure an environment conducive to sleep. But they didn’t address the road into Slumberland directly and expect you to close your eyes and wait until you “fall” asleep. They talked around the problem. All the questions remain: What do we know about going to sleep? Where does sleep reside? How do we get there? What has gone wrong?

You realize that some thoughts, what we might call the psychic voice, keep you from going to sleep, and you’ve tried to not think those thoughts, but the problem is that your mind has to think about something, and generally it is hot-button issues. If you quit one troublesome thought, something else comes to mind, and it is not conducive to sleep either. You need something for your mind to do that actually assists the going-to-sleep process. No one even addresses the need for this, much less supplies it. Oh yeah, “Count sheep.”

If you shouldn’t be waiting for sleep, how do you go get it? How do you hunt it down? To start this safari, we need to understand the wake-sleep transitional state. And interestingly enough, we know quite a lot, but that information hasn’t been directed toward getting to sleep. We generally think of our primary mental state as thoughts, which come from the psychic voice. What a thought is, on an objective basis, scientists are not quite sure, but we experience them continuously. What we don’t realize is that we cannot think without visualization. Aristotle was the first to recognize this. As he put it, “Without an image, thinking is impossible.” [On Memory, Ref 450a1] Images occur before thoughts. One might say that thoughts are built on images. Just as computers work most basically with zeroes and ones, the mind works with images.

We don’t see all the psyche’s activity and are probably clued into only a small portion of all that is going on. Some images do come to the surface, and the popular term for where these images appear is the “mind’s eye.” The mind’s eye is much more important than you might think, and it has nothing to do with eyeballs and everything to do with falling asleep. The mind is an image-processing machine. Archetypal psychology, an offshoot of Jungian psychology, is based on this fact. Here is the way archetypal psychologists view the images that appear in the mind’s eye:

The source of images – dream images, fantasy images, poetic images – is the self-generative activity of the soul itself. In archetypal psychology, the word “image” therefore does not refer to an afterimage, the result of sensations and perceptions; nor does “image” mean a mental construct that represents in symbolic form certain ideas and feelings it expresses. In fact, the image has no referent beyond itself, neither proprioceptive, external, nor semantic: “Images don’t stand for anything”. They are the psyche itself in its imaginative visibility; as primary datum, image is irreducible. [Hillman, James (2013-10-18). Archetypal Psychology (Uniform Edition of the Writings of James Hillman, Book 1) (Kindle Locations 118-122). Spring Publications. Kindle Edition.]

Exactly how mental images, those that do not involve the eye, are formed is not fully understood either, but one thing we all know is that dreams are built with images. In dreams, we see, and this is the key we’ll use to unlock the sleep problem. To sleep, we need a bridge from the World of Thoughts to the World of Images.

The method of getting to sleep presented in Chapter 4 can go a long ways toward helping you repair your sleep propensity curve. Sleep professionals will tell you to go to bed at the same time every night, and this is certainly good advice. But if you don’t go to sleep right away, it won’t repair your sleep propensity curve. The only way to repair it is to get to sleep at the appropriate time and stay there, night after night after night. Sleep, deep sleep, at the proper time is the only thing that repairs it.

In Chapter 2, we will unlock the most closely held secret mechanisms of the mind while it is trying to go to sleep, and in Chapters 3 and 4, we will direct those mechanisms toward producing sleep instead of wallowing in non-productive thought processes. Sleep is more complex than you ever thought, and getting to sleep once you understand what is going on is much easier than you can imagine.